SaaS Compliance Caveatsview page source ain’t what it used to be

I read Heather Meeker’s blog and highly recommend it. Her recent piece on open source compliance for SaaS vendors is another good one, with two big caveats:

-

It’s no longer safe to assume that client-side JavaScript will satisfy source requirements under copyleft licenses. It’s not the preferred form for making changes these days. It’s the preferred form for fast download, parsing, and execution.

-

Most SaaS companies keep their app code proprietary, including their JavaScript “front end”. Finding strong-copyleft code in your JavaScript bundle is about like finding strong-copyleft in your GUI app working tree. There’s no “Web exception”.

Transpiling, Bundling, and Minification

It’s now very common for SaaS app developers to run all their client-side code through several development tools before serving to users’ web browsers. The results are megabytes-large, borderline unintelligible blobs of thoroughly obfuscated code. It’s still technically JavaScript, but the kind browsers can run, not the kind devs would maintain.

It’s perfectly normal to see three types of build tools in recent front-end build chains.

To start, transpilers like Babel translate new and custom programming language syntax into older versions of JavaScript that visitors’ web browsers reliably support. These tools essentially “compile” dialects of JavaScript into an older, widespread, standard dialect.

Other transpilers, like the ClojureScript compiler, don’t even start with JavaScript. They translate some other language, like Clojure, into JavaScript. The results aren’t idiomatic, just functional. They use the JavaScript runtime like the Java Virtual Machine or Common Language Infrastructure.

From there, bundlers like Webpack and Browserify find all the libraries and frameworks that a piece of JavaScript code depends on and mush them into one big file, stuck together with glue code. This lets users’ browsers download all the code at once, instead of sending many requests for many source files to the same server. Some bundlers also optimize, removing parts of libraries that aren’t referenced or splitting a big bundle into logical chunks that make sense to load as pieces. New browser technology, especially HTTP/2, is starting to make all this less necessary.

Finally, minifiers like Terser and Uglify not only remove insignificant whitespace, but strip out comments, scrunch variable names, refactor control structures, and perform all manner of other tricks to minimize file size and facilitate compression. These tools rarely advertise themselves as “obfuscators”, but they get halfway there by optimizing without concern for readability. Any front-end dev who actually wrote and committed minified-looking code like this would be banished from teamwork immediately.

Along this chain, many tools also produce “source maps” showing what parts of their code inputs correspond to what parts of their code outputs. Taken together, those source maps allow web browsers to trace a path back from an error in the final client-side code bundle to a line and character position in a specific file of original source code. Debug versions of SaaS apps serve these source maps for developers. But companies rarely serve source maps—or the original source files they refer to—in production. Customers get only bundles of transpiled, minified code, which load much faster.

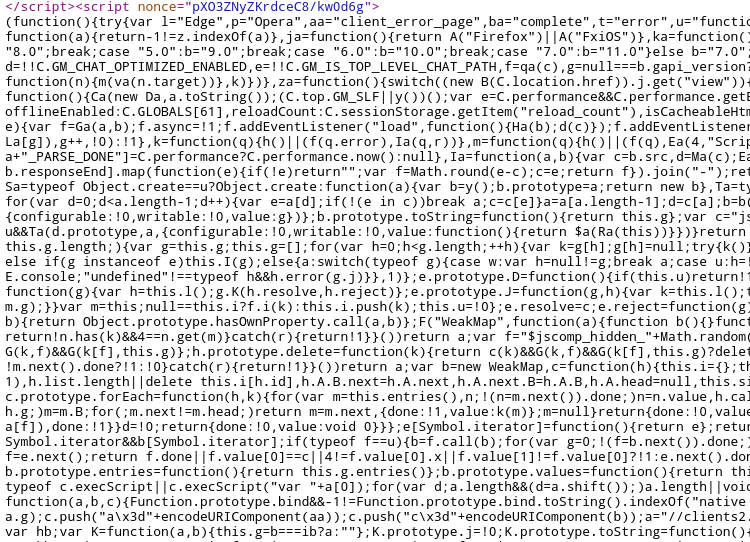

For a quick sense of how inscrutable JavaScript ends up, visit GMail and view source. The JavaScript I see embedded in the HTML page today is only a tiny fraction of all the client-side code GMail loads. It’s a giant JavaScript app. But I think we can get the effect:

Note that JavaScript keywords and API names like function and this and var and prototype remain. These will be handled well by the compression algorithms browsers and servers use, since they repeat so often. Note also that nearly all visible variable names—the names following var keywords—are but one or two letters. The programmers didn’t name their variables that way. The minifier renamed them.

If you asked me to add a feature or fix a bug in this code, it wouldn’t be a maintenance project. It would be a reverse-engineering project. If I found that this code was originally GPL licensed, demanded “Corresponding Source” from Google, and got told I already have it—just click “View Source”—I’d call license violation.

WebAssembly

This is the situation as I see it now, for many web apps. Granted, older apps and old-fogey programmers—apparently including me half the time—may still ship readable JavaScript. But if anything, we’re heading even more toward client code as an essentially compiled form of software.

WebAssembly, a standard kind of binary code for web browsers, isn’t so widely adopted as transpiling, bundling, and minifying. But some large and technically progressive firms are already using it in production apps. Rising-star programming languages, like Rust, already rely on it as compilation target for the Web.

We already see apps combining minified JavaScript and WebAssembly. Last I checked, a little bit of JavaScript’s still required to make WebAssembly run. But I foresee apps shipping entirely WebAssembly not too long from now. Unlike JavaScript, WebAssembly was designed from its start to load quick and run fast, and better fills that role. Hence “Assembly for the Web”.

Copyleft as Usual

When I started writing JavaScript eons ago, the use cases were much as Heather described: validating forms, basic interactivity. Also frivolous visual effects. Lots of frivolous visual effects. But all around: tiny additions to the built-in functionality of the web browsers. The magic happened on the server side, which is why we all got so used to URLs ending in .php and .asp.

We’re way past that now. Writing client-side JavaScript in 2021 can and often does look and feel a lot more like desktop or mobile application development, the kind of thing devs do with Java Swing, Qt, and Cocoa for installed apps. There are frameworks and runtimes for write-once, run-anywhere across desktop PCs, smartphones, and the Web. There are web apps where the “server side” is almost entirely commodity components—an authentication service, a database, a messaging gateway—that browser clients talk to directly.

All of that means more core functionality—the work SaaS companies tend to keep proprietary—gets “distributed” to the client side. It’s no longer safe to say that the “technology” is all on the server, with the client code merely adding sprinkles. A license compliance problem on the front end could be a real business problem.

Slip a GPL-licensed library into your client-side app, you have the GPL problem. Of course, the GPL was conceived long before JavaScript was a twinkle in Brendan Eich’s eye. And even recent versions of popular strong-copyleft licenses tend to speak in abstractions, rather than address interpreted languages or Web technologies directly. But I don’t think we lawyer types see those details as anything like end runs around license concepts like “work based on the Program”, not to mention legal concepts like “derivative work”.

For all those folks slinging front-end code in the SaaS business: Get yourself a license checker in CI and be grateful for good metadata. If they don’t exist for your language, get on that. A little prevention can save a lot of hassle.

Your thoughts and feedback are always welcome by e-mail.