The Developer Certificate of Origin is Not a Contributor License Agreementdispelling magical DCO thinking to reveal the system below

This post is part of a series, Line by Line.

To be able to use a piece of software you find online, you want a few things:

- the code

- a copy of the rules for using the code—the “license terms”

- evidence somebody actually applied those terms to the code—a “license grant”

- evidence that somebody actually had the legal power to apply those terms to the code—sometimes called “provenance”

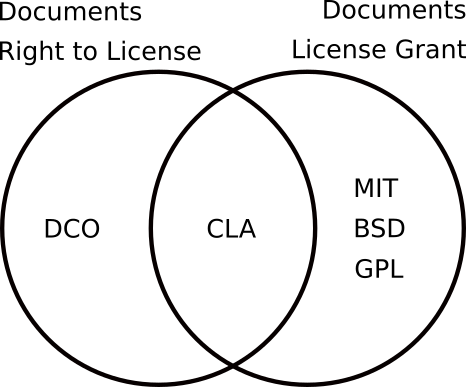

All software licenses, the DCO, and CLAs are just means to those ends:

The DCO

The Developer Certificate of Origin was written specifically for the Linux kernel development process. It’s short. We can read it, picking out the parts that help give us the assurances users want for open software:

By making a contribution to this project, I certify that:

(a) The contribution was created in whole or in part by me and I have the right to submit it under the open source license indicated in the file; or

(b) The contribution is based upon previous work that, to the best of my knowledge, is covered under an appropriate open source license and I have the right under that license to submit that work with modifications, whether created in whole or in part by me, under the same open source license (unless I am permitted to submit under a different license), as indicated in the file; or

(c) The contribution was provided directly to me by some other person who certified (a), (b) or (c) and I have not modified it.

(d) I understand and agree that this project and the contribution are public and that a record of the contribution (including all personal information I submit with it, including my sign-off) is maintained indefinitely and may be redistributed consistent with this project or the open source license(s) involved.

Two important notes:

First, the DCO repeatedly addresses having the right to license—provenance—both in the simple case of original code coming directly from one developer and in the indirect case of code being passed from developer to developer and eventually to Linus.

Second, the DCO assumes license terms appear in every file, and that license terms at the top of a file means work in that file is licensed under those terms. The DCO assumes open source licenses are “involved”, but doesn’t do the work of involving them.

There are still more important assumptions embedded in the DCO, which you can only really see by reading between the lines, or drawing on context:

First, the project is GPL, and specifically GPLv2. If you hack kernel code, you have only one valid choice of license: GPLv2. If you bring in code that was originally developed independently, it has to be under some permissive license “compatible with” GPLv2.

Second, “sign-off” means Signed-Off-By lines added to commits, such as with the --signoff flag to git commit. As patches come into mailing lists and pass from reviewer to reviewer, on their way up to Linus, a new Signed-Off-By gets tacked on at each step, documenting everyone who laid hands along the way.

Third, the Linux kernel is stuck on GPLv2, and will never get licensed on different terms. The kernel did not move up to GPLv3 when it was released, and as a practical matter, it probably couldn’t have if it wanted to. Too many people have contributed to the kernel. They, or their employers or clients, own the copyrights in their work. They never granted any broad license to the Linux Foundation or organization giving that organization the right to license their work under different terms.

Assumptions Reviewed

That’s a lot of assumptions. Let’s list them out together, in their most general forms:

-

License terms appear in every file.

-

Code files with license terms in them are licensed under those terms.

-

Choice of license terms for contributions are fixed in advance or tightly constrained.

-

Contributors are using

Signed-Off-By. -

Signed-Off-Byapplies the Developer Certificate of Origin to work in the commits where it appears. -

The project cannot or will not need to change its license terms in the future.

Assumptions 2, licensing of files, and 5, effect of Signed-Off-By, are fundamentally legal questions. Set them aside. Maybe in other blog posts, someday.

Of the rest: How many hold for your project?

Assumption 1, licenses terms in files, is a workflow choice. Sometimes this assumption will hold, as in many Java projects where files routinely begin with code comments. Sometimes it will not, as in many JavaScript projects, where license terms appear in a LICENSE file, or get referenced in package.json metadata.

Assumption 3, restricted choice of license terms, depends on the license applied to existing project code. For GPLv2 projects, this assumption largely holds. For GPLv2+ or GPLv3+ projects, there may be more of a choice, among versions of the GPL.

For MIT, BSD, Apache 2.0, Blue Oak, or other permissively licensed projects, there’s no safe assumption about license terms for contributions. Those licenses allow creating changes, additions, and other work on whatever terms developers wish, including commercial terms that nobody would call “open”.

I would argue that assumption 6 is never safe, not even for the Linux kernel. Courts might start interpreting or applying GPLv2 in unfortunate ways, as you see things. For example, they might weaken its copyleft rule or the clarity it provides about terms for patches and contributions. The law might also change in ways that require GPLv2 to be upgraded or fixed, to work as intended or to work at all. Locking in specific license terms brings all the welcome certainty of immutability, along with all its dangerous inflexibility.

An Actual CLA

The de facto standard contribution license agreement terms are the Apache Foundation forms. Many well known companies that use CLAs basically just fork Apache’s forms to replace “Apache” with their name, with few or no additional customizations. Once you know this, reviewing a lot of CLAs gets a lot easier. Diff against Apache first.

Apache’s CLA form for individuals, as opposed to companies, is only two pages long. Let’s look at the operative terms, skipping the initial definitions section:

2. Grant of Copyright License. Subject to the terms and conditions of this Agreement, You hereby grant to the Foundation and to recipients of software distributed by the Foundation a perpetual, worldwide, non-exclusive, no-charge, royalty-free, irrevocable copyright license to reproduce, prepare derivative works of, publicly display, publicly perform, sublicense, and distribute Your Contributions and such derivative works.

Here we have some license terms and a clear statement that they are being applied to some software, namely the contribution coming into the project.

If you’re thinking this looks familiar, you should. Compare the license grant in Apache 2.0. But it shouldn’t ring any bells about the DCO. We didn’t see any language like this in the DCO.

Notice also what’s missing from the Apache license. There aren’t any conditions about notice files or attribution or such. That means the Apache Foundations gets broader permission for the contribution coming in than they give out under Apache 2.0. But that also means the Foundation gets flexibility to license contributions under different terms—perhaps Apache 3.0—in the future. Apache’s CLA forms do not assume that it’s alright to lock projects into Apache 2.0 forever, without the ability to patch or replace license terms in the future.

Notice also that this is a copyright license, not a copyright assignment. Hence “contributor license agreement”. The contributor remains the owner of copyright in their contributions.

I’d argue the practical difference between assigning copyright and licensing copyright is way overblown. Especially for contributions to large, existing projects made available under open terms. But for those with knee-jerk aversions to the idea of assignment, it’s worth pointing out that that’s not what CLAs do. Calling a copyright assignment a CLA, or copyleft license agreement, is misnomer.

3. Grant of Patent License. Subject to the terms and conditions of this Agreement, You hereby grant to the Foundation and to recipients of software distributed by the Foundation a perpetual, worldwide, non-exclusive, no-charge, royalty-free, irrevocable (except as stated in this section) patent license to make, have made, use, offer to sell, sell, import, and otherwise transfer the Work, where such license applies only to those patent claims licensable by You that are necessarily infringed by Your Contribution(s) alone or by combination of Your Contribution(s) with the Work to which such Contribution(s) was submitted. If any entity institutes patent litigation against You or any other entity (including a cross-claim or counterclaim in a lawsuit) alleging that your Contribution, or the Work to which you have contributed, constitutes direct or contributory patent infringement, then any patent licenses granted to that entity under this Agreement for that Contribution or Work shall terminate as of the date such litigation is filed.

What we just saw for copyright, we now see for patents. Word-diff this with section 3 of Apache 2.0, you’ll see it’s overwhelmingly the same.

4. You represent that you are legally entitled to grant the above license. If your employer(s) has rights to intellectual property that you create that includes your Contributions, you represent that you have received permission to make Contributions on behalf of that employer, that your employer has waived such rights for your Contributions to the Foundation, or that your employer has executed a separate Corporate CLA with the Foundation.

This is the first provenance part of the Apache ICLA. Being “legally entitled” and “having the right” point the same way.

If you’re thinking this reminds of the DCO, you’re right on. It’s doing the same work. But where a lot of DCO language is overtly concerned with patches passing among multiple contributors and reviewers, the Apache ICLA is more concerned about whether individuals, as opposed to their employers or clients, have the legal right to license the contributions. That’s wise: a lot of software work falls under “work made for hire” rules and contracts, which make the employer or contract client, not the developer, the owner of copyright. As part of Apache’s CLA process, they often take both a corporate CLA from companies and individual CLAs from the developers.

5. You represent that each of Your Contributions is Your original creation (see section 7 for submissions on behalf of others). You represent that Your Contribution submissions include complete details of any third-party license or other restriction (including, but not limited to, related patents and trademarks) of which you are personally aware and which are associated with any part of Your Contributions.

Here we find echoes of the DCO’s language about original work and work brought in from others, who’ve already released under their own license terms. You can read “represent” as fancy pants legal for “say” or “promise” or “guarantee”. So this language puts the contributor on the hook for making sure they have the rights they need to contribute.

6. You are not expected to provide support for Your Contributions, except to the extent You desire to provide support. You may provide support for free, for a fee, or not at all. Unless required by applicable law or agreed to in writing, You provide Your Contributions on an “AS IS” BASIS, WITHOUT WARRANTIES OR CONDITIONS OF ANY KIND, either express or implied, including, without limitation, any warranties or conditions of TITLE, NON-INFRINGEMENT, MERCHANTABILITY, or FITNESS FOR A PARTICULAR PURPOSE.

Again, echoes of Apache 2.0, and of nearly all open software licenses, which routinely disclaim warranties, to avoid the developer being held financially responsible for problems with work they gave away for free in the first place. Notice that the language with ALL CAPS here is shorter than we see in Apache 2.0, MIT, or BSD. There are some cases where a contributor might be held legally responsible under this ICLA: when they made bad representations about having the legal right to license their contributions.

7. Should You wish to submit work that is not Your original creation, You may submit it to the Foundation separately from any Contribution, identifying the complete details of its source and of any license or other restriction (including, but not limited to, related patents, trademarks, and license agreements) of which you are personally aware, and conspicuously marking the work as “Submitted on behalf of a third-party: [named here]”.

Recall the DCO item (b), which talks about making sure work that isn’t yours comes under a good open license.

8. You agree to notify the Foundation of any facts or circumstances of which you become aware that would make these representations inaccurate in any respect.

If you signed a CLA, but it becomes clear people actually shouldn’t rely on the CLA you signed, that’s something the Foundation and Apache software users want to know about.

So What’s the DCO Good For?

The Developer Certificate of Origin does less than a contributor license agreement, like the Apache ICLA. But both DCO and Apache ICLA function as parts of systems designed to get all the work done. In review:

| DCO | GPLv2 | Kernel Flow | Apache ICLA | Apache License | Apache Process | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Original Work Provenance | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| Other Work Provenance | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ |

| License Terms | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| License Grants | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ | ✓ | ✗ |

| License Conditions | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ | ✗ |

| Documentation Process | ✗ | ✗ | Signed-Off-By |

✗ | ✗ | CLA Before Acceptance |

The Apache 2.0 license, the Apache individual and corporate CLAs, and the Apache house workflow were developed together, to work together. They fill each other’s gaps, interlocking to form a robust intellectual property management system for open software development.

GPLv2, the DCO, and Kernel Flow also work together as a system, in much the same way. They also fulfill each other’s assumptions. But they were developed more piecemeal.

The DCO turned out so specialized—a great fit for a few projects, and a terrible fit for most others—for several reasons.

For one, the DCO was the last part of the kernel system put in place. GPLv2 had already been written, and had already been applied to kernel code for a long time. Kernel flow was evolving and continues to evolve, but was already humming along at the time.

Second, the kernel is an incredibly important project, important enough to warrant kernel-specific legal work and process discussion. And other important software of the time, like Git itself, also used Kernel Flow. In 2004 and 2006, GitHub-style, pull request and hosted repository flow had yet to take off.

Third, the kernel’s importance brought it under legal fire from companies looking to claim a piece of, or forestall, its success. The DCO was most immediately a response to claims by SCO that parts of the Linux source code came not from Linus or other open software developers, but from the original UNIX source code licensed to universities and companies, which SCO had bought the rights to.

Linus and the kernel developers did not have written records showing where every line of kernel code came from, and who licensed it. That left SCO room to claim—unsuccessfully in the end, but annoyingly in the interim—that the code without documented provenance was theirs. The DCO and the Signed-Off-By process went into place to create that missing documentation going forward.

The claim wasn’t that parts of the kernel were contributed, but under the wrong license. That’s a license terms or license grant kind of problem, solved by CLAs for original work, and acceptable open source licenses for the rest. The claim was that contributors didn’t have the legal right to contribute the code at all. That’s a provenance problem, solved by the kernel’s license and procedures with the addition of the DCO.

Build a System

In contribution licensing, as in so much else, a project should think about its goals and risks, then make sure its terms and processes address them, to the extent they can at reasonable cost and inconvenience.

Some projects are so small, niche, or disposable, and always will be, that any investment in process is at best a form or practice or odd recreation. Some projects don’t face serious risk of provenance problems. Some projects want to lock into one, specific set of license terms for all time, risks be damned. Heck, most projects never get outside contributions. They arguably shouldn’t spend time or brain cycles on a process for handling them until they show up.

Unfortunately, too many projects clearly have both goals and risks related to contribution licensing, and either do nothing, process-wise, to address them, or downgrade from a complete system, like one with CLAs, to an incoherent, leaky hodgepodge, based on belief that merely saying the name “DCO” will ward off evil copyright spirits.

Some frank takeaways, putting all this together:

In my estimation, tacking the DCO onto a file like CONTRIBUTING.md and continuing on your merry way with pull-request-based development flow achieves next to nothing, other than deceiving yourself into thinking you’ve ticked a box. Squirreling DCO’s text away somewhere without a license, like GPL, that addresses follow-on licensing or a development workflow, like Kernel Flow, that involves developers invoking the DCO won’t crash your project immediately, or bring lawyers down upon you in a giant, teeming swarm. But if yours is one of the projects both lucky enough to matter and unlucky enough to have an issue, that is going to work about as well as the dusty old fire extinguisher left over by the last tenant that nobody ever bothered to check. In an emergency, it might contribute a small, disappointing mess to an already stressful situation. It will not save the day.

If you’re annoyed by CLAs, make them less annoying. Set up a CLA bot. Have people agree to terms via pull request comments, or add files to a subdirectory of your repo before merging. All of these are after-the-fact additions, like the DCO, to plug gaps in an incomplete approach to contribution management. GitHub did not ship with a go-to solution to contribution management for pull-request flow, and hasn’t anointed or first-party’d one, either. If your project needs that, you have to bring your own.

If mere mention of CLAs throws your or yours into panic attacks or fits of apoplectic rage, I’ve done what I can for you. Read up on the problems and how legal tools address them. Read some CLAs and understand them. Share this post if it helps. See also this earlier, shorter one, more on policy issues, or this one on why we’re still gap-filling GitHub, despite their terms of service.

CLAs and CLA processes document license terms, license grants, and good provenance. They don’t cast magic spells. If I send you a legal nastygram tomorrow, claiming that some part of your project’s code violates my client’s license terms, or was sent in by someone with no legal right to license it, what are you going to attach or link to in your response, to prove me wrong? That is the question. “We merged a PR adding DCO to CONTRIBUTING because we saw other projects doing it” is not an answer.

Your thoughts and feedback are always welcome by e-mail.