“Open Source” Is Nobody’s Propertyif OSI owned it, they wouldn’t be so touchy about it

You quit a mailing list, people send you links to archives. You quit Twitter, people send you links to tweets. You stop reading GitHub, people send you links to issues. I’m tired. I need something to link to.

This is a blog post, not a formal legal opinion letter that’s free and on the Web for some reason. I will publish this and sincerely hope that I never lay eyes on it again. If you need to make a decision about whether and how to dive the “open source” grab ball, hire a lawyer, or at least do some research of your own. Don’t read one blog post you like the sound of, stop, and blame me.

Here is the part that will tempt you: I see no evidence that the Open Source Initiative has any legal power to police the phrase “open source”. I see—and am sent—plenty of insinuation to the contrary. Hence this post.

I should mention that I have an interest here. I’ve taken flak for calling licenses, projects, and business models open source without any kiss of the Initiative’s ring. I still do. And no, it doesn’t bring me down.

It used to. If you’d asked me a few years ago about the Open Source Definition, I’d’ve sung its praises. Because praises are all I’d read about it on the Internet, since I was a kid. Mostly, as it turns out, on the OSI’s own website, and the websites of its patrons. Then I saw it in practice.

With the benefit of field experience, included but not limited to actually reading the Definition critically and a long look behind the curtains of OSI politics and process, I now see the OSI story as a two year triumph and a twenty year tragedy. The work OSI existed to do is long done, carrying off a marketing coup in 1998. What’s left is preserving that hallowed memory, and the wisps of buzz still gassing off it, as a wasting asset to 2020 and beyond. And minting credentials of proximity to the power that had been, at the beginning.

OSI now does more to stymie opposition to industry abuses than to galvanize it. It is like the startup that, having long since made its highest placed funders and founders rich, lumbers on in the trappings of a dated incumbent, courting unequal partnerships with patrons nearer their prime. In more practical terms, it’s unclear what initiative the Initiative has left, apart from policing the term “open source” across social media.

But there’s no such thing as police without law.

Legally, there is no registered United States trademark on the phrase “open source” for licenses, software, or computer services. As a result, nobody can deploy national trademark law in the usual way to stop you or me or anyone else from calling things “open source” without their approval or permission. The badge that a term policeman would wear, the seal on a trademark certificate, doesn’t exist.

I’m not a European lawyer, and don’t practice European law. But I don’t see any European registered trademarks, either. Unless you count the ones for Irish dairy.

Back in the States, OSI does have four registered trademarks to its name: registration numbers 86191623, 77414159, and 77414187 for OPEN SOURCE INITIATIVE, with and without logos, plus number 78813707 for OPEN SOURCE INITIATIVE APPROVED LICENSE. You can copy those numbers into The United States Patent and Trademark Office’s free status and documents database and click “Status” to see for yourself.

But wait! OPEN SOURCE is a substring of each of those marks, so the Open Source Initiative has trademarked OPEN SOURCE, right?

Wrong.

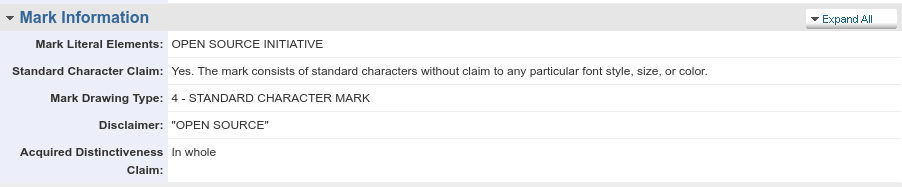

Expand the “Mark Information” section of any summary page on the Trademark Office’s website, you’ll see something like this:

Note the line:

Disclaimer: “OPEN SOURCE”

What does that mean, “disclaimer”? Aren’t trademark certificates about claiming?

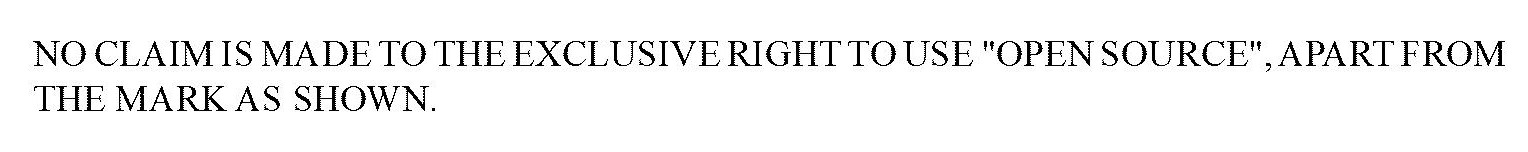

Pull down the registration certificates, like this one for number 86191623, and read for yourself:

In other words, the Open Source Initiative has an exclusive right to use OPEN SOURCE INITIATIVE and OPEN SOURCE INITIATIVE APPROVED LICENSE for certain kinds of goods and services. Those exclusive rights are called trademarks, a form of intellectual property. But the Open Source Initiative doesn’t have any trademark on OPEN SOURCE alone or as a substring of other, longer names and phrases. OSI “owns” the string OPEN SOURCE on the public record only as it appears in the longer marks it has registered.

Why would the Open Source Initiative file trademark applications not claiming OPEN SOURCE? It had to. As the organization itself admitted back in its heyday, when Eric Raymond was still president:

On June 15 1999 ZDNet broke the news that OSI’s application for an Open Source trademark had lapsed, anticipating the public statement OSI had planned to make following its board meeting on 17 June. Subsequently, many people have expressed concern that the phrase “Open Source” might be trademarked by some party hostile to the open-source community.

That’s not likely, for the very reason the application was permitted to lapse. We have discovered that there is virtually no chance that the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office would register the mark “open source”; the mark is too descriptive. Ironically, we were partly a victim of our own success in bringing the “open source” concept into the mainstream.

So “Open Source” is not and cannot become a trademark. The purposes for which OSI sought a trademark, however, are still valid. We believe the open-source community gains much from the existence of a recognizable brand name — one which certifies to users that software is being distributed under the licensing model best shown to produce high quality software. We believe that software vendors will seek to use an appropriate certification mark to signify that quality.

Actually, it’s a bit more complicated than that. OSI didn’t apply to trademark OPEN SOURCE. Software in the Public Interest, the corporate home of Debian, did, before OSI existed. That older application hasn’t been fully digitized, but you can find the relevant metadata easily enough. You can dig up the messy political brouhaha about transferring control from SPI to OSI, too.

In the end, the application for OPEN SOURCE full stop was abandoned. I wasn’t privy to that process, but I can guess why neither SPI nor OSI bothered meeting the deadline for a response to the Trademark Office’s objections. Once they got a lawyer involved—none was listed on SPI’s application—that lawyer would have told them their application was doomed. The phrase “open source” was too descriptive. What’s more, it was already in use. Rather played out, in fact.

Some words and phrases are easier to claim, defend, and enforce as trademarks than others. At the top of the food chain are “fanciful” marks like KODAK and XEROX. These are essentially linguistic greenfield, made-up words with no existing usages to run afoul of. Below those lie “arbitrary” marks, which do have existing meaning, but not any meaning to do with the goods, service, or company using the mark. Think APPLE for computers. There follow “suggestive” marks, which not only have existing meaning, but have meaning that suggests some quality of the good or service offered by the business. Think GREYHOUND for bus transportation.

At the bottom of the hierarchy, we have “descriptive” marks. These amount to little more than commonly understood statements about goods or services. As a general rule, trademark law does not enable private interests to seize bits of the English language, weaponize them as exclusive property, and sue others who quite naturally use the same words in the same way to describe their own products and services. We don’t take chips off free speech, even commercial free speech, so lightly.

It is possible for a description to become a trademark in time. But only by collecting a lot of compelling evidence, over a long span, showing that a descriptive word or phrase has actually morphed into a codeword pointing exclusively to a specific provider of goods or services in the common tongue. On the flip side, even well protected fanciful trademarks can lose protection if they become so popular that they become synonymous with a good or service, no matter who provides it. Think “hoover” for “vacuum cleaner” in the UK.

The phrase “open source” is woefully descriptive for software whose source is open, for common meanings of “open” and “source”, blurry as common meanings may be and often are. If I’d never heard the phrase “open source” before, and a new client came to me next week asking about using and protecting the name, I’d strongly advise them to invest in something they can own, instead. There’s an infinitude of potential names out there. Why pick one you can’t get, or can only get in a tenuous, contestable way at great expense?

We can see the descriptiveness of “open source” in action before OSI began in 1998. Plenty of people used the terms “open” and even “open source” before SPI tried to trademark it. Here’s a use of “Open Source” from 1993 in a mail archive … of a list about Windows software. Here’s Caldera using it in a marketing release for DOS in 1996.

And of course we can see it used since OSI for all manner of projects, companies, and initiatives proceeding without their blessing. Just follow the Term Police on social media and track their targets, one after another, month after month, year after year. Every usage OSI partisans feel compelled to stomp on is that much more evidence of the damage that legal rules against trademarking descriptive statements defend us from. So is the broader, consistent pattern of new uses popping up all the time, and the need to “correct” them.

In fact, tacking “open” onto “source” seemed just as inevitable before OSI as it does now. The meaning of “source” isn’t really the issue. The meat, “open”, had done decades of service in industry marketing by the time the Open Source Initiative came around. To the point of feeling fairly well sucked dry.

Christine Peterson, who suggested “open source” at the O’Reilly-brokered meeting that kicked off the OSI media blitz, wrote that she initially ran the idea past a friend in marketing, who warned her that “open” was already vague, overused, and cliche. A whole book, Open Systems: The Reality had been published in 1993 on the proliferation of competing, vague definitions of “open” by software and hardware vendors in the decades before. The editors found a single flicker of clarity through the chaos from a 1991 conference attendee:

It took me a long time to understand what (the industry) meant by open vs. proprietary, but I finally figured it out. From the perspective of any one supplier, open meant “our products.” Proprietary meant “everybody else’s products.”

This was long before the birth of the Open Source Initiative. But not before the birth of the Open Software Foundation in 1988—a decade before OSI—which later merged with X to form The Open Group, which is still around.

In short, “open” was an easy word to like, an easy word to sell, and an impossible word to control, the apple of discord of computer salesspeak. It was and remains a vague, connotation-positive generalism whose metaphorical potential dwarfs its literal meaning, even in everyday speech.

A whole generation of IT buyers had latched onto that potential before the Internet era, or even the dawn of personal computing, as the rallying cry of newfound buyer-side leverage. And a whole corresponding generation of IT vendors, sprouted up where IBM had failed to take root, took notice, tapped in, and fairly well sapped it to dust by a million ads, trade show pavilions, press releases, and conference talks. Everybody was “open”. So nobody was.

The O’Reilly-facilitated working group that set out to rebrand “free software” sans Stallman either never saw this history, failed to learn its lesson, or genuinely thought they’d be the first to call “open” truly their own, like the treasure under a tree. Their successors have had to face harsh reality more squarely.

Cue this awkward page entitled “International Authority & Recognition” on the OSI’s website circa 2015, plus the more recent “Affirmation of the Open Source Definition” of last year.

The “authority” page drips with language designed to imply power without any demonstration of it. Long on words, short on action. Tellingly, none of the sources cited in the English language bestow any “power to enforce obedience or compliance”, OED’s relevant sense of “authority”, on the Open Source Initiative’s definition, process, or approval. We can expect that some reflect no more or less than the extent to which the institution of OSI fits institution-shaped holes in the logics of other institutions. Still others boil down to mere testimonials and name drops.

Testimonial is the whole substance of the more recent “affirmation”. The need for such a call to circle the wagons did more to confirm the tenuousness of OSI authority than to reinforce it with anyone not already riding in the train. Authority was feeling tenuous because for the first time in a decade or more, OSI was seeing interesting new license submissions. For the first time in a decade or more, its assumed function seemed to matter.

All of these performative announcements and wordsmithing pufferies would be rendered immediately and totally unnecessary by a single, seven-digit United States trademark registration number. Here’s my personal certificate for WAYPOINT for downloadable legal forms. No testimonials, back scratching, or name-drops needed. And no disclaimers. Trade on my name, I’ll sue and get a court order. Not that I’ll have to. The mark is a public record.

Those vested in the Open Source Initiative don’t have that, and they know it. But rather than accept that intellectual property law simply doesn’t cover what they want to license—the phrase “open source” for legal terms and software remains in the public domain—they contrive to control it as if they owned it, and to convince developers and companies that they do, by other means. Every statement of OSI’s assumed authority—OSI defines open source, software isn’t open source unless OSI approves—should be read with an implicit “should” and an unstated “OSI says”. OSI says OSI defines open source. OSI says software shouldn’t be called open source unless OSI approves.

This explains the constant temptation to short-circuit debate by invoking authority of law, to use “lawyers say” like sudo in “sudo make me a sandwich”. OSI partisans make some better arguments for discipline in use of the term. In my opinion, none particularly strong. But a surprising number of weaker arguments boil down to “Respect our authority!” and a willingness to pronounce the exclamation point.

Of course, even if the law hasn’t explicitly recognized “open source” as anyone’s property, the law never draws perfectly sharp lines. And of course it doesn’t prove negatives. I’d be remiss to pretend the desperate and crafty couldn’t pull a few frayed edges of the facts and the law.

United States federal trademarks, for one, aren’t the only kinds of trademarks, even in the United States. Firms can also make trademark claims under the laws of specific states, at least for business done within those states. But there are reasons—both legal and practical—that we look first and foremost to federal law when it comes to trademarks.

Symptomatically, I could name dozens of lawyers who’ve helped clients apply to register federal trademarks in the last year. I couldn’t name anyone I’m sure has done a state registration or claim in the past five. By impression, state trademark claims are for litigators to drag out when something goes very wrong with the client’s first-choice federal claim. And of course for cannabis companies, the exception to everything, whose business has been decriminalized and even specifically regulated under some states’ laws, but remains illegal under federal law.

Conceding trademark entirely, OSI might also dig for claims of deceit and unfair dealing, arguing that whether it controls the use of “open source” or not, its definition reflects ironclad consumer expectations, and those expectations are grievously and knowingly exploited by anyone saying “open source” without meeting their standards, as they interpret and apply them. That is, of course, circular. It is also counterfactual, on at least two levels.

The Open Source Definition was originally the Debian Free Software Guidelines. The Debian Free Software Guidelines were written on a private mailing list, evidently without legal input, then announced as fait accompli, more than twenty years ago, attached to the Debian Social Contract. Open Source Initiative mailing list regulars decry “crayon licenses” written without legal input or public feedback. But they sanctify a “crayon definition” produced in just the same way. Sanctify it in a way that Debian, where it originated, does not.

I believe such a document falls well short of the kind of objective evidence of widespread, shared understanding required to show either the “acquired distinctiveness” needed to turn a chunk of English into a trademark or the kind of predictable, damaging commercial deception amounting to a breach of fair competition. To claim deceit based on that kind of unilateral territory marking is to presuppose a consensus that does not exist, on the basis that a great many people who don’t know of the claim haven’t formally contested it through the claimant’s own privately established process.

Looking again past words, and to actions, all of this handily explains OSI’s reluctance to heed repeated calls for open-minded, independent surveys of how developers actually understand the phrase “open source”, what they know, if anything, about the Open Source Initiative or its Open Source Definition, and what essential connection, if any, they see between them before they’re indoctrinated into the OSI line or shouted down for straying from it. I get the sense they’re afraid of what they’d find. The accursed “GitHub generation” made a lot less hay than the old guard, but there are way, way more of them.

In the end, falling back on the fuzz of the law is just that: a fallback, a last resort. In the United States, federal trademark registration isn’t the gold standard, it’s the greenback, the everyday coin of the branding realm. If they’d ticked that box, the answers would be simple. Since they haven’t, at best they can wave hands in threatening ways.

Thus, overall, based on the research I’ve been able to squeeze in over the years and notes picked up along the way, no person and no organization owns the phrase “open source” as we know it. No such legal shadow hangs over its use. It remains a meme, and maybe a movement, or many movements. Our right to speak the term freely, and to argue for our own meanings, understandings, and aspirations, isn’t impinged by anyone’s private property.

That right extends to debate about how we ought or ought not use the term, for OSI partisans as well as those annoyed, bemused, and abused by them. But that debate must be won by reason and suasion, not harassment and naked claims to authority.

There are only dogs in this fight. No masters.

Your thoughts and feedback are always welcome by e-mail.