Don’t Rely on OSI Approvalactivist approval does not track practical needs

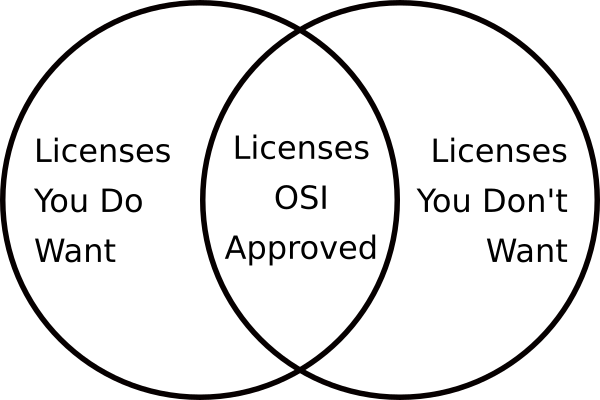

Relying on Open Source Initiative approval to get the kind of software license you expect is almost always trouble. For nearly any practical need, the OSI-approved list will green-light licenses you don’t want, and red-light many you do.

There are valid and wise ways to rely on OSI in policy advocacy, where a nonprofit can go and say where and what you can’t. But relying on an advocacy organization to approve legal terms for legal needs is different. It’s category error.

I have criticized the Open Source Definition and the way the Open Source Initiative claims to apply it. Not here. In this post, I hope to draw attention to simple mismatches of need, purpose, and perception that afflict terms and policies that incorporate OSI approval by reference.

I help clients draft contracts, policies, and other terms all the time. More often than not, those terms deal with open source software. What license will the developer apply to their work under contract? What licenses can they accept for the work of others they use on the job? What kinds of projects will a service host, or host for free? How will a nonprofit share work they do under a grant?

Every time I’ve answered one of those questions by referencing OSI approval, I came to regret it. Using what I learned from those experiences, I’ve helped clients make others regret it, too. All of that was totally avoidable.

Unless your purpose is to track OSI political history or bolster OSI esteem, don’t define “open source” by OSI approval in written rules, and don’t incorporate OSI’s list of approved licenses by reference for consistency or completeness. OSI applies some analytical rigor to licenses. But also institutional expedience, thought-leader fashion, prevailing activist strategy, and internal politics. Expedience, fashion, activism, and politics do not leave much room to correct analytical mistakes, or even to acknowledge them. As a consequence, OSI’s license list is littered with problematic outliers.

You can read nearly all licenses that OSI has approved on opensource.org. You can verify they’ve been approved for yourself.

To choose and advise on open source licenses responsibly, for specific, practical needs, we have to look past the fact that a license appears on opensource.org, and contend with what it says.

Copyleft

By far the most common misunderstanding is that all OSI-approved licenses make software available for building commercial projects, products, and services. If that is true at all, it is only technically true.

Making it practically true has been a longtime goal of some activists working through OSI. But they have not succeeded in convincing industry to meet all the demands of approved licenses. If your company makes commercially available software, chances are your business model implies a licensing model that conflicts with significant OSI-approved license conditions. If you allow software developers on your team to use software under OSI-approved licenses, expecting OSI approval to guarantee business-friendly terms, you may get copyleft terms designed to change the way business works instead.

Software licensing wonks distinguish “permissive” and “copyleft” licenses. You should, too.

Roughly speaking, permissive open source licenses give everyone the right to do nearly anything with software, for free. That includes building other software that’s licensed under typical commercial terms, as opposed to open source terms. It includes building software that isn’t licensed, or even shared, outside a company at all.

The MIT License is a common permissive license.

Copyleft open source licenses, by contrast, require sharing and licensing new software built with copyleft-licensed software as open source. Specifically, you must share code in the best way for others to make changes, and license under open source terms. Perhaps you hadn’t planned to be so generous.

The GNU General Public License, Version 3 is a common copyleft license.

Copyleft licenses differ in how much they require you to share, and when you’re required to share. But all copyleft licenses require sharing in at least some situations. Under many copyleft licenses, it’s occasionally hard to tell whether you have to share or not, even with professional help.

I wish copyleft were simpler. I’m working on that. I wish more software developers and businesspeople understood how well copyleft can serve their goals. I’m working on that, too. But when it gets right down to it, if permissive open source is free candy, copyleft is a free puppy. If you want a puppy, a free one is great. If you don’t want a puppy, receiving a free one by surprise can be costly and awkward.

If you define acceptable licenses as whatever OSI approves, expecting permissive candy, you may receive surprise copyleft puppies. For example, if your company sponsors “open source” development, delivery under OSI-approved license of developer’s choice, you may discover that you have to pay twice: first to have it made available under a license you can’t accept, then again for an exception to that license’s rules, or to have the software made again from scratch. Specify a particular license, or a process for choosing a license, instead.

Vintage Copyleft

Even if you see copyleft coming, you may not get the copyleft you expect. The effect can be a bit like trying marijuana for the first time since the Summer of Love. The old stuff is still around. But chances are good that your new experience will be less of a throwback to yesteryear, and more of a catapult launch to the present.

When many practitioners think copyleft, they think “GPL” or “GNU General Public License”. There are a few versions of that license, the best-known of which is version 2. You’re likely to run into it.

GPL 2 got a lot of press in the late 1990s and early 2000s. Sensational press. At the time, straight-laced firms eyeing open source as a tune-in, drop-out threat to their order invested heavily in writing and telling scary stories about GPL 2 copyleft. Hard-won intellectual property was practically throwing itself out of office windows, it was said. The scarier the story, in general, the less likely it was to be true, and the more likely it was to be heard.

Industry promptly conceived various coping mechanisms for resulting managerial anxiety. An entirely new consultative sub-practice, a kind of licensing-industrial complex, spontaneously self-organized to sell cures for the common copyleft, in equal and opposite reaction to how terrifying it was made out to be. Some of that opportunity empowered those who knew whereof they spoke to get heard and paid for a change. But few and cautious were the wise, many and loud were the bold, and peddlers of cartoonish compliance training, materials, and programs canvassed the land. We still suffer their consequences.

If your compliance approach to copyleft code is really a compliance approach to GPL 2 as conceived by an itinerant PowerPoint jockey circa 1999, you are likely to have ingrained shortcuts, rules of thumb, and certain dubiously crafty, rumor-borne trickeries for avoiding obligations to release company code as hippy fodder. Dynamic not static linking. Avoiding “distribution” in myriad ways. Gating software releases on audit and verification. Some of these make sense. Some are “but I didn’t inhale”.

Times have changed. Copyleft has changed. OSI has approved new copyleft licenses. GPL 2 is no longer state of the art.

GPL version 3 wants more code, brings merry license pranks to the brave new world of patents, and expresses entirely new, idiosyncratic moral conditions. The Affero GPL is wise to the most reliable weakness of its copyleft brethren—sharing software as a service instead of software to install—and takes pains to close the loop by tying a big new legal knot in it. The Open Software License, also in many versions, reads like a business lawyer wrote it, because one did. It carries itself straight-laced and sportsmanlike, pulling no punches and abiding no tricks. The Reciprocal Public License, approved in two versions, requires code even if you don’t “distribute”, and even more than GPL and friends. It reads like a contract pasted together by a lay legal savant, ransom-note style, and it just might have been.

These stronger copyleft licenses aren’t so popular as old GPL 2, which had quite a heyday. But if you invite OSI-approved, new copyleft may welcome itself to your party. Mistake it for GPL 2 at the door, and it will nod politely, snicker off to spike the punch, nurse a quiet rage, and eventually make a scene.

I am altogether in favor of better, stronger copyleft licenses that work as intended and say what they mean in terms non-wonks can manage without Motrin. It’s hardly a bad thing to understand these licenses, appreciate them, and especially to deploy them tactically, potentially with irreplaceable effect. But the dark source of much of their power remains the element of enterprise surprise. They are esoteric, but OSI approved. Even many folk savvy to open source remain blissfully ignorant of their innovations.

Don’t get caught thinking GPL 2 vintage 1991, and swallowing AGPL 2007.

Patent Coverage

Permission to use software is almost always a matter of copyright law. Less often, it is also a matter of patent. But when a patent does cover a program, the implications can be gravely expensive. Patent infringement with software is low-probability, high-cost risk, and therefore essential to your ability to use without getting sued, the very privilege an open software license is supposed to bestow.

Reviewing and approving licenses implies a certain amount of legal savvy. OSI has had access to fantastic legal talent over the years, both in-house and volunteer. But those expecting OSI-approved licenses to uniformly address the patent problem may be rudely disappointed.

The first issue is old license forms. Many of the most popular public software licenses are also the oldest, or descended from the oldest. “BSD” and “MIT” terms come down from notices written up by university tech transfer offices in the 1980s. Widespread legal involvement in open software, and due concern for the existence of patents thereon, didn’t make the scene until near 2000, around the time of OSI’s birth.

The old “academic” licenses are generous, but it’s not clear from their terms whether that generosity extends to patents. There is hope, in the form of various rules of background law that might say what the licenses don’t. But unless and until a clear case under an academic open source license hits the record, those licenses entitle users to pay lawyers to argue implication, not an explicit patent license that obviates the need.

Then there’s the absolute outlier, the Adaptive Public License, with this quirky check-the-box patent worksheet:

Part 6: Patent Licensing Terms

For the purposes of this License, paragraphs A, B, C, D and E of this Part 6 of Exhibit A are only incorporated and form part of the terms of the License if the Initial Contributor places an “X” or “x” in the selection box alongside the YES answer to the question immediately below.

Is this a Patents-Included License pursuant to Section 2.2 of the License

YES

[ ]NO

[ ]

And the kicker:

By default, if YES is not selected by the Initial Contributor, the answer is NO.

Under APL, by default, you get no patent license. And no room left to argue an implied one.

OSI declined to approve Creative Commons’ popular CC0-1.0 public domain dedication for saying “no” on patents without offering any box to check for “yes”. But the result for CC0 did not change the result for APL.

If you require an OSI-approved license thinking patents won’t be a problem, a crafty counterparty can give you a license that never says the word “patent”, or a license that does say “patent”, but also says “no”, instead.

No Public Domain

Relying on OSI approval on patents can not only leave you without patent protection when you expect it, it can also stop you using perfectly safe software under popular patent-less terms when there aren’t any patents to worry about. Sometimes, patents simply aren’t a practical risk. Instead it’s the policy that’s the problem.

CC0, mentioned above, is worth mentioning again. It’s tremendously popular in government and academe. A great deal of important work comes out under those terms, which aren’t OSI-approved.

Likewise self-styled releases into the public domain, without use of CC0 or any other standard notice. That software isn’t available under an OSI-approved license, or any license at all. But using it may pose far less legal risk than software clearly licensed under a bad OSI-approved license.

OSI-approved licenses are not the whole world of software that can be downloaded, shared, and used for free. If you rely on OSI approval to pre-approve every form you’re likely to want, you’ll spend a lot of time filling in the gaps ad hoc.

Missing Permissive Licenses

Even when software is available under an explicit permissive license, OSI may not have got around to approving it. Or OSI may have intentionally refused to approve it, despite it being quite like many others that it has, to discourage “license proliferation”.

Discouraging multiple licenses that say essentially the same thing is noble. But nobility doesn’t pay when you or your team need a particular piece of software under a less-common set of terms, and find yourselves stuck under an OSI-blinkered compliance program. OSI may very well have approved an equivalent license for software you don’t care about, and on the basis of that approval refused to approve the license for the software you do care about, because proliferation.

As of May 2019, a quick automatic cross-comparison of Blue Oak Council’s more comprehensive permissive license list and a data file of OSI-approved licenses yields a hundred and twenty licenses that Blue Oak certifies, but OSI hasn’t approved. That number probably isn’t exact. But it’s roughly a hundred and twenty chances that OSI approval will be a choke point rather than a shortcut.

OSI-approved licenses are not the whole world of perfectly dependable permissive license forms. Relying on OSI approval for that kind of completeness is folly, too.

Standardized Compliance

In much the same way that many copyleft compliance programs focus specifically on GPL 2, know it or not, many standardized approaches to attribution—the terms of open source licenses that require compiling notices of license terms and copyright notices for open software—focus on the typical without accounting for OSI-approved aberrations. Treating every license like MIT or BSD can leave you out to dry.

The clearest issues concern what OSI pejoratively calls “badgeware” licenses. These OSI has dissed, but also paradoxically approved.

The most important example, the Common Public Attribution License, goes well beyond the typically kind of credit-and-copyright required by more typical terms:

As a modest attribution to the organizer of the development of the Original Code (“Original Developer”) … the Original Developer may include in Exhibit B (“Attribution Information”) a requirement that each time an Executable and Source Code or a Larger Work is launched or initially run (which includes initiating a session), a prominent display of the Original Developer’s Attribution Information (as defined below) must occur on the graphic user interface employed by the end user to access such Covered Code (which may include display on a splash screen), if any. The size of the graphic image should be consistent with the size of the other elements of the Attribution Information. … If the Original Code displays such Attribution Information in a particular form (such as in the form of a splash screen, notice at login, an “about” display, or dedicated attribution area on user interface screens), continued use of such form for that Attribution Information is one way of meeting this requirement for notice.

In other words, CPAL allows developers to demand opening credits in software applications, rather than mere mention in the liner notes. This may prove an issue if you planned to put your own logo there, and haven’t any process for doing otherwise.

The OSI-approved Attribution Assurance License is quirkier still, leveraging cryptography to ensure the author gets exactly the credit they require:

Redistributions of the Code in binary form must be accompanied by this GPG-signed text in any documentation and, each time the resulting executable program or a program dependent thereon is launched, a prominent display (e.g., splash screen or banner text) of the Author’s attribution information, which includes: (a) Name (“AUTHOR”), (b) Professional identification (“PROFESSIONAL IDENTIFICATION”), and (c) URL (“URL”).

Placing these credits in a “legal notices” list or “open source disclosure” deep in a help screen won’t cut it.

There are other traps for the unwary, often requiring the distribution of specific files. the_frameworx_license.txt under the Frameworx Open License 1.0. NOTICES under the Apache License, Version 2.0, a favorite piece of expert trivia. license.txt under APL again. And on the licensor side of things,manifest.txt under the LaTeX Project Public License, Version 1.3c, complete with a scary (and dubious) warning that if you don’t provide one, “the licensee would be entitled to make reasonable conjectures as to which files comprise the Work.”

You may expect such abberrations in your mental model of what OSI has approved. But that is for naught if the process you or your charges follow, or the tools you use to automate that process, fail to account for or comply with the aberrations. Disputes on matters of credit especially have a tendency to become indignant and ego-charged.

Legal Rigor

I’ve mentioned above that not all OSI-approved licenses dispose of patents responsibly. Alas, OSI has also approved at least one license that, to my legal eye, fails to handle much of anything responsibly. A fundamentally broken license.

With sincerest respect to its lay author, whose heart was in the right place, promoting plain brevity in legal terms, the Fair License cuts too deep, to the point of rendering itself legally defective. As open software licenses go, Fair seems to want to do the right thing. But it fails to say the right words to do so. In its entirety:

<Copyright Information>

Usage of the works is permitted provided that this instrument is retained with the works, so that any entity that uses the works is notified of this instrument.

DISCLAIMER: THE WORKS ARE WITHOUT WARRANTY.

This is what some OSI participants pejoratively term a “crayon license”. I have no doubt that the license author will not be suing or threatening anyone for their work under these terms. But the appearance of Fair in the wild gives no guarantee of similar intentions from others who choose it. If anything on the OSI approved license list is fair play, Fair is, too, and that’s probably not so fair to your reasonable open source expectations.

Like other outliers among the OSI-approved, Fair’s weakness is both an excusable and an exploitable flaw. I could make an argument that Fair does not allow making changes to the software licensed, for example. No one expecting “open source” should have to hear that argument.

English

If you were thinking, worse comes to worst, you can always buckle down and review OSI-approved terms yourself, you ought to be aware of three licenses in Québécois: Licence Libre du Québec Permissive, Réciprocité, and Réciprocité forte. Translations are provided, but OSI’s pages make clear those translations aren’t OSI-approved.

I don’t read French, and can’t tell you what the original texts mean, much less under Quebec law, which I don’t practice. Perhaps it couldn’t be worse than the tangle-terms some American drafters have got approved. But if I were going to pick a kind of license to read in a second language, it wouldn’t be one called “reciprocal strong”. That’s a refreshingly straightforward way to describe the most complex kind of copyleft.

I mean no cultural disrespect. I’ve come to feel at home in three natural languages in my time, and while English is my first and best, it is not my favorite. I strongly support the creation and use of open source licenses for and from other language communities, as a matter of principle. But principle is as far as I can go and be helpful.

I can schmooze over Lorca or Borges, flip through Bely or Blok. But I can’t advise clients on complex license terms in those languages. I know enough to know better.

Perhaps:

any license approved by the Open Source Initiative in English or OSI-approved English translation

But I’ve never seen that in the wild. In any event, it would still prove over- and under-inclusive, for all the other reasons above. The misapplication of OSI advocacy approval for legal function can’t be mended so easily.

Alternatives

In my experience, most folks who don’t already know about aberrations among OSI-approved licenses say “open source” and mean something far more specific: as many permissive public software licenses as they can handle in more or less the same way as possible.

Blue Oak Council, a nonprofit collaboration of open licensing lawyers I recently helped to kickstart, came together around shared need for a list of just such licenses to use in building policies and terms. When advising small and nonprofit companies, whether on compliance, grants, or contracts, my colleagues and I routinely sought approaches to open source licensing that unlock as much open source as possible, without stepping into the relatively small number of complex licenses outliers.

A published, updated license list was the missing piece. We each had our own incomplete version of it. Those turned out to be almost entirely consistent, lawyer to lawyer, and therefore easy to combine and refine. Also to show in action, in example language for various kinds of terms, from sample company policies to contract snippets. If you’d like a sense of how to spec open source licenses more specifically than via OSI approval, with practicality first in mind, have a look.

Encouraged by success there, Blue Oak is exploring similar materials on the copyleft side of open source. That’s a bit more complex. But I hope we will have a similar list and examples to share for those interested, and soon. Smarter building blocks for smarter terms and policies.

Avoidance

I’ll end not with embracing copyleft complexity, but eschewing the complexity of open source licensing altogether. Sometimes all of this simply isn’t worth thinking about. Consider whether for your particular need, the fact that software or its source code is published online, rather than private, might be enough on its own.

This has been the approach of current-generation software development services, like GitHub, Travis CI, and npm, from very early on. Nearly all of these providers encourage standardized licensing, including under OSI approved terms, by policy. But their requirements for free service dodged the question. In fact, their policies on licenses were and are little read and little known. The requirement to publish or pay was simply a feature of their software.

If that works for your need as well, it is usually far easier to express and administer. You needn’t police license terms, and won’t be pulled into opinion or policy debates about OSI or particular approved or not-approved forms. You’ll seem neutral.

Every long-working open source developer can tell sad stories of good code found on the Web, abandoned without sign of any license, that could have been part of something greater, but languished in licenseless obscurity instead. Those are real costs, or rather losses of real value, that might have been avoided by a more prescriptive policy about what licenses would have been allowed on the hosting service. Perhaps losses within your responsibility or concern. Perhaps not.

At the same time, many platforms that welcome public but licenseless code also welcome the lion’s share of new open source developers. By inviting new talent to explore licensing when ready, rather than derailing many off the learning process by requiring a free choice of “correct” license as a password of entry, early on, these platforms may in fact foment more well licensed work in the end, as larger matriculating classes of newbies yield larger cohorts of seasoned, license-informed pros. Most developers pick up licensing as they go, as a relatively tiny part of a comprehensive open source education.

What approach seems best to you, either for your needs, for contribution to a greater open source movement or effort, or for both, is up to you. When you make a choice, whatever the nature and balance of your motives, I think open software is best served by complicating your engagement with a minimum of unwelcome license surprises.

By pointing out where a common shortcut takes a toll of that kind, I hope these notes will help make your work with open source more fulfilling.

Your thoughts and feedback are always welcome by e-mail.